CULT HEROES

Public figures who are greatly admired by a relatively small audience or share influence impartial to commercial success. Artfully cobbled together by our own protagonist, Paul 'Simmo' Simpson.

In January 1995, hauled up before an FA panel that could have banned him for life after he had been red carded and kung fu kicked a fan, Eric Cantona decided the best way to make amends by apologising to the governing body, Manchester United and the “prostitute who shared my bed last night”. Luckily, most of the panel didn’t hear that last bit and an astounded David Davies, the FA’s head of media, soon realised he was joking.

Loved and loathed in unequal measures, by turns inspirational and incomprehensible, frequently baffling but seldom, Cantona is the very definition of a cult hero. He could, as his most patient manager Sir Alex Ferguson said, “see spaces on the pitch that I couldn’t see from the bench”, but was also, as Capital Gold commentator Jonathan Pearce remarked, after his unexpected display of martial arts at Selhurst Park, a man of “wicked temperament” whose place in the game was always precarious. He had already retired once, even before he arrived in England in 1992, after telling each and every member of a French league disciplinary they were an “idiot” and, after coming back from his six-month ban, to win two more Premier League titles and one FA Cup with Manchester United, he hung up his boots for good in the summer of 1997. He was a bit portly by then – even sporting a double chin – but was still only 30.

In the 1990s, when most English players stuck to boilerplate rhetoric, being alternately ‘sick as a parrot’ and ‘over the moon’ in interviews, Cantona mused cryptically about seagulls, trawlers, and sardines. He was always unapologetically himself, whether that meant playing with his shirt collar up, saying his proudest moment was “kicking the hooligan”, or crossing the historic divide between player and manager by having a cup of tea with Ferguson in his office before training.

You can be greater than Cantona and still be a cult hero – as Muhammad Ali, James Hunt, Diego Maradona, and Ronnie O’ Sullivan all show – but you also can be much, much worse. Andy Clarke, who toiled upfront for Wimbledon in the 1990s averaging a goal for every ten appearances, endeared himself to Dons' fans because, as one put it: “He was the epitome of an incredibly limited player promoted from the Conference to the Premier League and valiantly trying to make the best of it.”

The contrasting examples of Cantona and Clarke illustrate a paradox about cult heroes in sport. Even as fans, we don’t want too many of them. A team composed entirely of Cantonas or Clarkes will never win anything. This is not, as some argue, a consequence of the globalisation of sport, it’s a consequence of sport. As Bill Shankly said, when defining the perfect football team: “You need eight men to carry the piano and three men who can play the damn thing.”

Dustin Brown

“Most people have a fist pump, he also had a knee pump,” tennis aficionado Impetus describing Brown on the Talk Tennis forum.

In 2023, even Dustin Brown’s dog had given up on him. At one point, the German-Jamaican tennis star’s back pain was so acute that he could barely walk 300m. As Brown (aged 40) recalled: “My wife normally walks the dog so when I took him, he was probably looking at me thinking ‘Please can I go with mum?’” Miraculously, last July, he competed at Wimbledon for the first time since 2019, impressing in the men’s doubles alongside Argentina’s Sebastian Baez.

Born near Hanover, to a German mother and Jamaican father, Brown was gifted, passionate and poor. At first, he travelled to tournaments in a Volkswagen camper van, which his parents bought with a loan. “That was my mum’s idea,” he said. “Back then, if you lost in the first round you earned around $117.50, basically about enough to buy enough gas to drive to the next tournament. And I was stringing racquets for other players. Different times but it got me to where I am.”

Although he never ranked higher than No. 64, he was, as William Skidelsky, author of Federer and Me, wrote: “A flamboyant presence in an increasingly uniform sport. He is professional tennis’s nearest thing to an eccentric. No one else looks like him. No one else has his repertoire of on-court antics (the celebratory leaps, the eight-foot-high racket tosses). And certainly no one else plays like him.”

Impetus, an aficionado on the Talk Tennis forum, pithily captured Brown’s style: “3.8kg extra weight in his Rastafari hair. Most people have a fist pump. He also had a knee pump. Preferred shots: dropshot, tweener, lob, stop volley and smash. Last resort shots: Backhand and forehand. Style of serve: Flat and fast first serve. Flat and fast second serve. Best hands on the tour.” Standing 6ft 5in tall, he confounded opponents with a body that seemed to consist almost entirely of arms and legs.

Brown was climbing up the rankings in June 2014 when, at Germany’s Halle Open, he beat Rafael Nadal in straight sets. Skidelsky observed: “Actually, beat is too polite a word. Pulverised would be better.” With the first set tied at 4-4, the underdog won seven games in a row reducing Nadal to a bit-part player with a dazzling repertoire of aces, returns, volleys and slam dunks.

Thirteen months later, Brown did it again, this time at Wimbledon, knocking Nadal out in the second round, 7-5, 3-6, 6-4, 6-4. That upset was as much about strategy as skill. As he said: “Any of the guys at the top I beat, I got them out of their comfort zone and forced them to play my tennis.” That tactic won him two doubles titles and defeated the likes of Marin Clinic, John Isner, and Alexander Zeverev.

His career was ultimately stymied by appalling back injuries. In February 2017, three points from victory in a match in Montpellier, a disc in his back went and he left the court in tears. He was never entirely fit again, missing Wimbledon for four years and, in 2023, was told the disc had ruptured internally, leaking liquid into his spinal cord.

Brown’s fleeting return – in the men’s doubles at the French Open and Wimbledon last year – is testament to his determination to train through the pain barrier but provided his last hurrah and, aged 39, he reluctantly retired. John McEnroe summed up the paradox at the heart of this maverick career: “He’s in the top 10 when it comes to low percentage shots, but not in the top 100 on high percentage shots.”

Zlatan Ibrahimović

“He’s a very humble guy and worked every day to improve. He’s proud of himself too, he loves being the best,” Juventus coach Fabio Capello.

There is nothing you can say about Zlatan Ibrahimović (43) that he hasn’t already said himself. Comedian and actor Billy Crystal made that point about Muhammad Ali, the Swedish footballer’s great hero, back in 1979. And with his autobiography I Am Zlatan, candid – too candid? – interviews and social media posts, modern football’s most accomplished nonconformist has followed his idol’s example.

Growing up with a Croatian mother and Bosnian father in Malmo, Ibra never adhered to the Swedish code of Jante – essentially ‘don’t think you’re better than anyone else’ – making his name in street football games as a master of the ‘no-look’ pass. He once described his playing style in these terms: “I went left, he went left. I went right, he went right. I went left again; he went to buy a hot dog.” Although ‘jumpers for goalposts’ style pundits harrumph about the decline of the authentic ‘street footballer’, the Swede’s career shows how problematic transitioning between the two forms of the game can be. When he joined Ajax in 2001 the club’s staff realised that he lacked pace, didn’t know where to run, when to pass and, despite being 6ft 4in tall, wasn’t great at heading the ball.

The young player was honest about his limitations, admitting when he joined Ajax: “I’d never really thought about football before.” The sound of 50,000 fans whistling at him made the learning curve even steeper and after some games he locked himself in his Amsterdam apartment. At Malmo, his first professional club, his team-mates had been united in awe of his talent but also his habit of shooting at the wrong time from the wrong place. Ajax scouts had decided he was worth the risk after seeing him lob the ball over one defender, and back-heel it past another to score. (He was lucky they didn’t watch him on the day he head-butted a team-mate for a tough tackle in training.)

As Ibra’s game matured – a process that accelerated when he signed for Juventus in 2004, worked hard in the gym and put on 10 kgs of muscle – many of his ‘wrong’ shots produced the right outcome. The most memorable example being the acrobatic bicycle-kick with which he scored from 30 yards out in a 4-2 win against England in November 2012, a strike opposing manager Roy Hodgson likened to a “work of art”.

In truth, the Swedish star never came to see football in exactly the same way as players and coaches who had been steeped in the system since they were seven or eight. Ultimately, this mindset destroyed his relationship with manager Pep Guardiola at Barcelona. His single mindedness was a weakness but also his superpower. As former Scotland manager Andy Roxburgh says: “Sometimes, the best tactic against the defensive block is a brilliant soloist.” Ibra’s street footballer unpredictability certainly infuriated Guardiola (and some team-mates) but it also demoralised opponents. He loved to draw defenders towards him, confident that, with his sublime close control, he could take one, two or three of them on and, magically, emerge with the ball.

Ibrahimović was never a natural fit for Guardiola’s philosophy, founded on the three Ps (play, possession, and position) especially in a side constructed around Lionel Messi. After Barca lost the 2010 UEFA Champions League semi-final to Jose Mourinho’s Inter – the Swede was substituted in both legs – his frustration boiled over and he told the coach, in front of the team, “You’ve got no balls”. He expected to thrash things out in an argument with Guardiola but was frozen out instead.

If the Swede didn’t quite cut it at the very top, as a strangely persistent urban myth in English football suggests, it’s hard to explain how and why he impressed such exacting coaches as Fabio Capello and Mourinho. At Juventus, Capello made him watch videos of Dutch forward Marco van Basten’s movement and finishing, recalling: “Ibra got it straight away. He’s a very humble guy and worked every day to improve. He’s proud of himself too, he loves being the best.”

He only played one season under Mourinho at Inter but they won the Serie A title and Coppa Italia together. He shouted at the Portuguese coach too, demanding to be substituted against Siena, after the Nerazzurri had clinched the Scudetto, because he was, to be blunt, hungover. Mourinho deliberately misunderstood him, throwing the player a bottle of water and telling him: “Here, take a drink and go.” Minutes later, the furious forward scored the goal that made him Serie A’s top scorer that season.

A league champion in France, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain, Ibrahimovic is the only player to score for six UEFA Champions League teams (Ajax, Barcelona, Inter, Juventus, Milan and PSG), remains Sweden’s all-time record goal scorer with 62 goals and in 2021/22, when he was more than 40, secured his fifth Serie A title (with Milan) while playing with a damaged anterior cruciate ligament. Such feats prompted the Tifosi and media to call him: “Ibracadabra”. He once summed up his career with brilliant, hubristic, brevity: “First, the talent controlled me. Then I controlled the talent.”

Kimi Räikkönen

“I know the things he’s doing, he’s doing very carefully. The rest is his private life, and if you’re famous, good-looking, and financially successful, you can enjoy your life,” Eric Boullier, Lotus team manager.

Winning a Grand Prix as efficiently – in other words, slowly – as possible never inspired Kimi Räikkönen (45). He always drove fast – whether he was racing a kart (where he made his name), a motocross bike (which he rode without telling his bosses in F1), a snowmobile (in 2007, he won a race in Finland registered as his hero James Hunt), a powerboat (while dressed as a gorilla) or the Ferrari, in which he won the 2007 F1 title. He even, twice, tried his hand at Nascar

Entering a race under Hunt’s name was something, the Finnish star confided, “my friends and I had always joked about,” adding: “My life would have been so much easier if I’d raced in the 1970s. I was definitely born in the wrong era.” He was, for a time, almost as much of a party animal as Hunt and, after too many vodkas, was spotted cavorting on – and falling asleep over – an inflatable dolphin in a nightclub. When asked about such episodes, he replied: “What I do in my private life doesn’t make me drive any slower.”

That may be the most memorable thing he ever told the media. In his post-race interviews, he made taciturn Czech tennis ace Ivan Lendl look as loquacious as Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Asked once what his first words had been as a baby, he replied: “My parents have told me, but I don’t remember. I’m no good at remembering.”

As a driver, his single-minded dedication to winning, extraordinary unflappability and Finnish nationality earned him the nickname ‘Iceman’. Just over thirty minutes before his first F1 race, in the 2001 Australian Grand Prix, the other members of his Sauber team realised, in a panic, that he was missing. An engineer eventually spotted him napping at the back of the garage. Such low-key preparation worked because he came sixth, earning a point.

That mattered because many people in F1 felt that the 21-year-old, signed by Sauber after 23 entry level races, had been promoted too far, too soon. He did well enough for McLaren to hire him to succeed his compatriot, Mika Häkkinen. Although he twice finished second in the world championships, he didn’t really suit McLaren’s disciplined, corporate ethos and, slightly implausibly, engineers blamed him for pushing fragile cars beyond their limits. He was recruited by Ferrari in 2007 after thrashing their first-choice drivers Michael Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello at the Belgian Grand Prix in 2004.

In Australia in March 2007, the Finn became the first driver since Nigel Mansell in 1989 to win a Grand Prix on his Ferrari debut. He still took time to adapt to his new car and Bridgestone tyres but never complained publicly and ended up matching his own – and Michael Schumacher’s – record of ten fastest laps in a single season. Twelve podium finishes and six victories, including the season finale, the Brazilian Grand Prix, were enough to clinch the title for Räikkönen, one point ahead of Fernando Alonso and Lewis Hamilton.

Although the ‘Iceman’ raced for another 14 seasons – for Ferrari, Lotus, Ferrari again and Alfa Romeo – he only won six more races in F1. That shouldn’t obscure his gifts as a driver: in 352 races, he made the podium 72 times without starting in the front row.

In an age when sports stars routinely behave like divas, Räikkönen was refreshingly down to earth. Asked once how he wanted to be remembered, he said: “I don't want to put some kind of limits on how you remember. I mean, I don't care much because I have luckily been able to do most things how I wanted to do them. Whatever they remember, good or bad, it's a memory and that’s fine for me.”

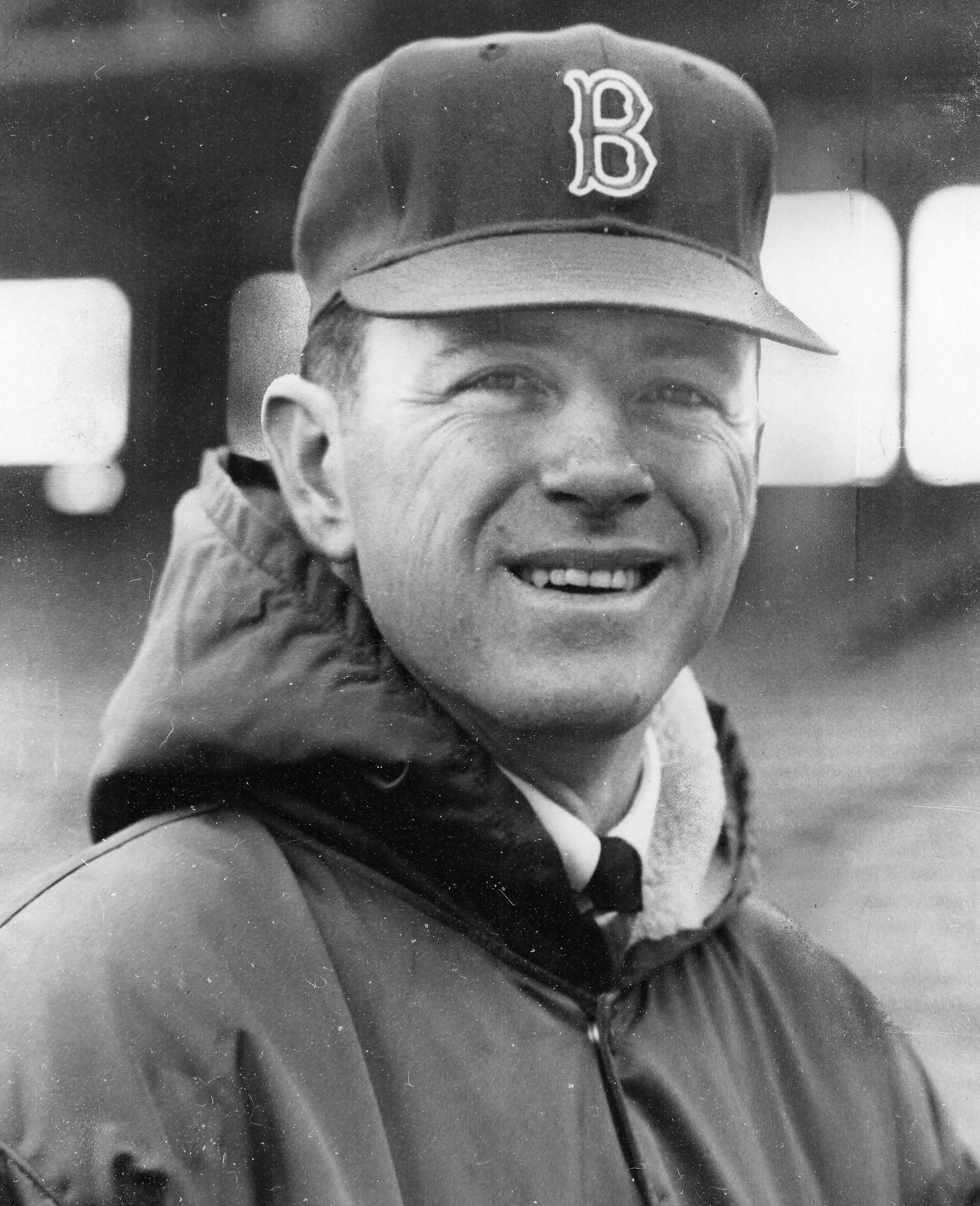

Dick Stuart

“No one is indifferent to him. The other day [our fans] had a fight in the stands over him,” Bill Crowley, Boston Red Sox PR man.

Baseball slugger Dick Stuart (1932 – 2002) was variously dubbed ‘Stone Fingers’, ‘Dr Strangeglove’, and ‘The Ancient Mariner’, that last nickname alluding to a line in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem: “It is an ancient mariner, and he stoppeth one of three.” All of these tags were inspired by his abject incompetence in the field. Baseball journalists Brendan C. Boyd and Fred C. Harris famously reported: “Stu once picked up a hot dog wrapper that was blowing toward his first base position. He received a standing ovation from the crowd. It was the first thing he had managed to pick up all day, and fans realised it could well be the last.” At least in Japan, where he scored 48 home runs in two seasons for Yokohama, fans hailed him as ‘Moby Dick’.

Stuart certainly knew how to bat, scoring 228 home runs for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Boston Red Sox, Philadelphia Phillies, New York Mets, Los Angeles Dodgers and California Angels between 1958 and 1969. Some of those hits bordered on superheroic: in 1959, he scored with a 457ft strike at the Chicago Cubs. He won the World Series in 1960 with the Pirates – their first title since 1926 – but even when he was most effective in 1961, his 35 home runs only told half the story: he struck out 171 times, more than any other batter.

Whether he was positioned at first base, or anywhere else, Stuart operated on the premise that less (movement) was more, which makes it all the more remarkable that he made more mistakes than any other fielder in the National League in 1958, 1959, 1960 and 1961. Once, in pre-season training, the announcer reminded fans that anyone who interfered with the ball in play would be ejected from the ballpark”, prompting a coach to quip: “I hope Stuart doesn’t think we mean him.” The batter, shrewdly, refused to be fazed by all the criticism, joking: “Other ball players have loyal fans, I have loyal hecklers.”

As Red Sox PR chief Bill Crowley recalled: “No one is indifferent to him. The other day we had a fight in the stands over him. A guy ran down to the fence and began to yell things at Stuart, when a big guy in a blue shirt grabbed the one with the megaphone and belted him a couple of times. Out on the field, Stuart is going like this with his fist, as if to say, ‘Attaboy, give it to him.’”

A part-time movie extra, Stuart controversially agreed to host his own TV show before arriving in Boston. When Red Sox coach Johnny Pesky asked: “Dick, do you know what you’re doing?”, he replied, “No John, I don’t think I do.” What he did grasp, presciently, was that sports was already becoming part of the entertainment industry, once remarking to a colleague, after smoothing his uniform, tightening his belt and adjusting his cap: “I put 20 points on my average if I know I look bitching out there.” Once complaining that he would have scored many more home runs if he hadn’t had to chase so many “bad pitches”, he added: “People know me. Whether they like or dislike me, I don’t mind.”

Andre van Troost

“Standing a full 13-feet tall at the crease, wild of hair and long of limb, the erstwhile Flying Dutchman bowled balls so fast they barely stayed within the confines of Taunton,” Wisden.

The roll call of brilliant Dutch cricketers is only slightly longer than the list of great Swiss admirals but Andre Van Troost (52), described by some opponents as the fastest bowler of all-time, would probably be up there, so why isn’t he better known?

Partly because Van Troost, oblivious to the anguish of Somerset fans in the 1990s, never enjoyed bowling to a consistent line and length. As he told Mail Online, he never knew which version of himself would turn up: “Honestly, on a good day, I could have played Test cricket. On a bad day, I wasn't good enough for Somerset seconds. I had no idea each morning which it would be – it depended on how many burgers I'd had.” In 71 First-Class matches for the county, he took 146 wickets.

Not only did he have no clue where the ball would end up, he didn’t always know where his run up would start. Even so, he managed to overcome such existential quandaries, dismissing Nick Knight, Brian Lara, Alec Stewart, Graham Thorpe, and Mark Waugh, taking 3-27 to help the Netherlands overcome West Indies in a limited over match in 1991 and racking up 13 wickets in nine internationals in the ICC Trophy, at an economical average of 17.38.

Van Troost was 15 when he was spotted by Somerset captain Peter Roebuck on the county’s tour of the Netherlands. As a right-arm fast bowler, the Dutchman’s credo was: “Stick it up ’em, let ’em have it.” He didn’t worry about the wicket, he aimed at rib cages and catches to short leg. As he recalled: “When I hit someone, the slips loved it.” He did, though, regret fracturing the cheekbone of West Indies captain Jimmy Adams.

His modus operandi was brilliantly captured by Wisden: “Standing a full 13-feet tall at the crease, wild of hair and long of limb, the erstwhile Flying Dutchman bowled balls so fast they barely stayed within the confines of Taunton. He famously broke his hand during a second XI match for the county when his arm swing after bowling another thunderbolt delivery was so elongated, excessive, and committed, that it smashed into the pitch, snapping a bone.”

With an offer to play for England mired in bureaucracy, and his back playing up badly, van Troost began to find the treadmill of county cricket with Somerset – driving to Durham, stopping at Essex on the way back, before playing at home in Taunton, and trying not to fall asleep at the wheel – “a bit of a drag”. He retired at the age of 26, briefly running the Dutch cricket association. Even in his mid-thirties, he loved the game enough to turn out as a batsman for local side Schiedam.

When the ‘Flying Dutchman’ faced Surrey at the Oval in the mid-1990s, he consistently bowled at over 100mph, according to England batsman Mark Butcher, who said he made Waqar Younis look medium paced. Although Shoaib Akhtar, Brett Lee, and Shaun Tait have all, records suggest, topped that, Van Troost must be one of the fastest bowlers never to play Test cricket. His only rival for that ambiguous honour is Duncan Spencer (53) who, coincidentally, was plagued by back problems – suffering four stress fractures in his first four seasons at Kent and Western Australia – and, despite some ill-starred comebacks, effectively retired at the age of 26.

Whereas van Stroot was actually 6ft 7in tall, Spencer was only 5ft 8in, prompting Australian wicket keeper Ryan Campbell to joke that he had “a V8 engine in the body of a Mini”. Laid off with life-changing injuries in 1996, he had taken Nandrolone as a painkiller – not realising it stayed in the system for 18 months – and was banned. (At one point, he was in such agony he could barely dress himself.) He did, though have the satisfaction, in a Sunday League match between Kent and Glamorgan in 1993, of bowling at the speed of light against – and almost dismissing – his boyhood idol Viv Richards. Although Kent lost, the West Indian legend told Spencer: “That’s the quickest bowling I’ve ever faced – and on a slow wicket.”

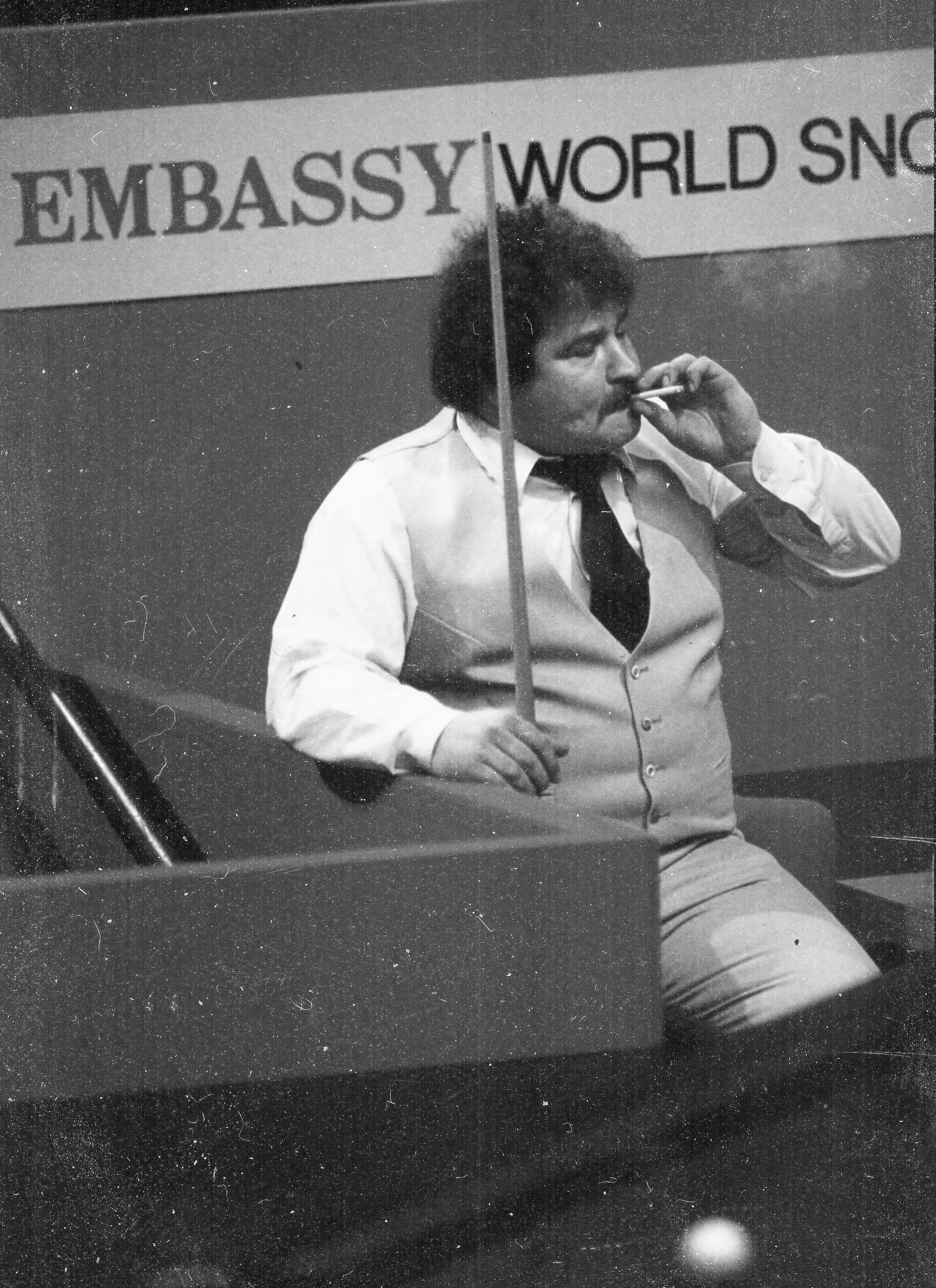

Bill Werbeniuk

“Bill was a larger-than-life character who played the game against all the odds,” John Virgo.

Serial world snooker champion Stephen Hendry had no hesitation when The Guardian asked him to nominate his match of the century: “Bill Werbeniuk versus an old Scottish pro called Eddie Sinclair. Werbeniuk won 43-42. That’s pints by the way. Went on all day, the drinking, finishing when Sinclair was on his back, unconscious.” At that point, the Canadian (1947 – 2003) declared: “I’m away to the bar now for a proper drink.”

The most extraordinary aspect of Werbeniuk’s snooker career is that he even had one. Diagnosed with a tremor in his cue arm, he decided the best way to manage it – accounts differ as to whether this was based on medical advice – was to consume vast quantities of alcohol. Typically, he downed at least six pints of lager before a match, and drank another pint for every frame, claiming to have consumed 76 cans during one fixture. (For a while, his spending on lager was accepted as a tax-deductible expense.)

Because Werbeniuk had hypoglycemia (a condition associated with diabetes which dramatically lowers blood sugar) his body burnt off alcohol incredibly quickly. On the downside, his weight ballooned to 20 stone, an embarrassing handicap in an era when players were all but contractually obliged to wear tight trousers. In 1980, in a Team World Cup match against Dennis Taylor, he split his trousers while leaning over the table. Werbeniuk made the audience laugh, pretending that someone had farted, asking: “Who did that?”.

All that said, the Canadian was no mere novelty act. In 1982, he won the Team World Cup for Canada, alongside Kirk Stephens and Cliff Thorburn. He was ranked eighth in the world in 1984/85, reached four world championship quarter-finals and, in 1985, against Jo Johnson played what commentator Ted Lowe described as the ‘pot of the century’, sinking a red into the bottom corner by bouncing the cue ball over another red that was in the way. The odds on such a pot are unscientifically estimated at a billion to one which may explain why, even though the shot was technically a foul, it was allowed to stand.

Outside snooker halls, Werbeniuk never gave the impression of taking life – or himself – too seriously, living for many years in a converted bus, near Worksop’s snooker centre. His attitude may have been influenced by his unusual childhood in Winnipeg, in the 1950s. His father, he admitted, “was one of the biggest fences in Canada who committed armed robberies, peddled drugs and every other larceny”. Honing his snooker skills in the family billiards hall, he earned quite a few bucks touring North America with Thorburn before turning professional.

In 1990, Werbeniuk’s career ended abruptly. Doctors had prescribed beta-blockers for his heart but these were banned by the International Olympic Committee as performance enhancers and, despite his appeals, he was fined and suspended, retiring to Canada where he died from heart problems at the age of 56. Even John Virgo, who was on snooker’s disciplinary committee at the time, thought he was unlucky: “If a doctor prescribes you a drug for health reasons, you should be allowed to continue with your job. In any other career would be – but not sport.”

Watching the Canadian heading off to the practice tables with a cue in one hand and a bucket of ice containing six cans of lager in the other remains one of Virgo’s favourite memories of snooker. Above all, it was a glorious reminder that, as he put it, Werbeniuk was a larger-than-life character “who played the game against all the odds.”

Miruts Yifter

“Miruts has been everything to me. When I started running, I just wanted to be like him,” Haile Gebrselassie, arguably the greatest long distance runner of all-time.

“Men may steal my chickens, men may steal my sheep, but no man can steal my age.” That was how Ethiopian runner Miruts Yifter (1944-2016), a tiny, balding figure, elliptically dealt with journalists who wanted to know whether he was 36, 40 or 42 when he triumphed in the 5,000m and 10,000m finals at the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Whatever the truth, he was significantly older than any other medallist in both finals. His burst of speed in the last 300m of each race inspired one of BBC commentator David Coleman’s finest rhetorical flourishes: “There goes Yifter the shifter! That’s why they call him the shifter! He really is flying!”

Yifter is largely forgotten outside his homeland today, deprived of the many titles his talent deserved by a toxic combination of bureaucratic incompetence, authoritarian government, revolutionary turmoil and Cold War politics. A factory worker and truck driver before he was recruited to run for the Ethiopian Air Force, he reached the 5,000m and 10,000m finals in Munich in 1972. He won bronze over the longer distance, with Lasse Virén, aka the ‘Flying Finn’ clinching gold. Before the 5,000m final, his coaches left Yifter in the mixed zone to warm up for so long that, by the time they had all reached the track, the race had started. Branded a traitor by Ethiopia’s tyrannical government, he went straight to prison.

He kept fit by running with fellow prisoners, enduring the guards’ occasional beatings, and earning a ‘get out of jail’ card to race in the 1973 African Games, where he won the 10,000m and came second in the 5,000m. He was deprived of the chance to win two golds at Montreal in 1976 by an African boycott, protesting against New Zealand’s inclusion (the Kiwi rugby team had recently toured apartheid South Africa). He triumphed over both distances at the IAAF World Cups in 1977 and 1979 but, given the conventional wisdom that distance runners peak in their mid-twenties, was not deemed a favourite in 1980. Unperturbed, he told the media: “Count my enthusiasm not my age. You need Ethiopian motivation to win.”

At the climax of the 10,000m final in Moscow, Yifter sprinted past the two runners ahead of him with the nonchalance of Usain Bolt in his prime, covering the final 200m in 26.8 seconds. As the Ethiopian approached the line, he raised his left arm in a clenched fist celebration. His victory in the 5,000m final was less spectacular but convincing. These races were, he said, carefully planned: “The 300m is the ideal mark – not too late, not too early. I listened to the movements of my opponents until five laps remained and decided on my course of action. Before they could reassert themselves, I would make my move.”

Having also set a world record for the half-marathon of 62 minutes, 57 seconds in 1977, Yifter probably expected a senior scouting or coaching role back in Ethiopia but officials distrusted him, associating him with the outgoing Marxist government. Emigrating to Toronto, Canada, he eked out a living as a coach before succumbing to respiratory illness at an indeterminate age in 2016. What we can determine is that he lived up to the promise of his first name Miruts which roughly means ‘the chosen one’.

Yifter was an icon to one young compatriot who became one of athletics’ greatest icons. Listening to the 1980 Olympics on the family radio in Ethiopia, seven-year-old Haile Gebrselassie was left awestruck: “Miruts has been everything to me. When I started running, I just wanted to be like him. He is the reason for who I am now.”

With two Olympic golds, four world championships over 10,000m, plus four consecutive wins at the Berlin Marathon, Gebrselassie is probably the greatest long-distance runner of all time. He learned his trade the hard way – running 10km to school with books tucked under his left arm – but it was Yifter who persuaded him that poor Ethiopians could aspire to greatness.